How Asperger’s Powers My Writing

A lot of people only see the bad sides of Asperger’s. What they don’t see is that it can have its perks, too. My entire career as an author—which is a very fun one!—is entirely dependent on this condition.

A lot of people only see the bad sides of Asperger’s. What they don’t see is that it can have its perks, too. My entire career as an author—which is a very fun one!—is entirely dependent on this condition.

Bad depictions in popular culture foster the narrative of the lazy narcoleptic: They’re lazy. They’re late/unproductive/lethargic employees. They’re uncaring lovers or absent friends. And so on and so on.

Pete’s autism is portrayed over and over again as being non-stop pain and suffering. That got incredibly hard to read; do people really think this is what autism is like?

When we talk about disability and sci-fi/fantasy, the first thing many will think of is the magical disability trope. But what does this trope entail and imply? And how can you subvert it?

I was intrigued by the virtual-reality premise, but this book is a veritable hotbed of misogyny and a case study in how not to write a wheelchair-using character.

In science-fiction and fantasy, you invariably run into fictional disabilities and allegories. Do these “count” as disability? What makes them work successfully in a book?

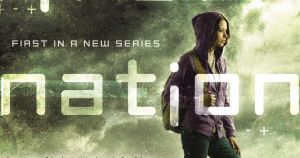

The description for this book uses the phrase “brilliant but autistic” to describe its main character, and that’s where our conflicted feelings about Viral Nation start.

Many characters who may be mentally ill reject treatment out of hand, considering therapy a waste of time and suspecting medication will turn them into a zombie. Why are these narratives so popular? What are the alternatives?

Insecure autistic boy meets thoughtful, magical adventure: The Real Boy is now my go-to recommendation when people ask for books with autistic protagonists.

Despite some flaws, it is clear the author did his research. I enjoyed this book and recommend it.