When you want to portray an autistic character, how do you do it—especially if you are not autistic yourself?

One approach is to describe visibly autistic things we do (“behaviors”): meltdowns, handflapping, not making eye contact, making social gaffes, taking things literally. These are shown in contexts where a non-autistic person wouldn’t have the same reactions. The reader is expected to see us as autistic because our behaviors are shown as out of place. The autism is being located in the behavior, which is shown as wrong for the situation, or, for positively viewed behaviors, at least as unusual for the situation.

Here is a key insight to creating realistic autistic characters: Autistic people do not do the visibly autistic things we do because of “autism,” full stop. We do things because, like non-autistic people, we are responding to our experiences of the world, and one of the characteristics of being autistic is that our experiences of the world differ from those of non-autistic people.

Sensory difficulties can make the world louder, more painful, more overwhelming. Social difficulties make the world more confusing and unpredictable. Eye contact can be so distracting that it prevents us from attending to what someone else is saying. It may look like we’re in the “same” situation as a non-autistic person, but our actual experience can be very different!

The upside of different experiences is that some situations present us with more fun. Some situations offer the chance to pattern-find, and using skills and talents can give a sense of flow and accomplishment. Some situations offer information relevant to special interests, which can be great! Some situations are safe for autistic people to stim in (e.g., handflapping, repeating noises), which many autistic people find pleasant and relaxing.

Our external circumstances can differ, too. When other people identify us as autistic, or acknowledge that we are autistic, they change their behavior towards us in ways that are sometimes helpful and sometimes not. Bullies and abusers sometimes target autistic people because we are often more socially isolated and sometimes visibly identifiable as different. Some parents expend major resources on trying to make their kids no longer (visibly) autistic, which can include abusive therapies. On the upside, when people know we are autistic, we may have more access to both formal and informal accommodations, like people being more understanding when we can’t go to loud and noisy places because of sensory issues. Other people’s responses to us are incredibly important because they are major drivers of our experiences.

Representations in fiction impact how people think of us. This can have direct consequences for our real-life experiences. A behavior-only portrayal of autism—one that locates autism in our actions rather than our experiences, one in which they are portrayed as out of place in the (assumed normal) situation—conveys (intentionally or unintentionally) that behaviors can be eliminated without reference to the reasons we do them. Let’s call this a behaviorizing portrayal of autism, because it shows our actions without the context of experience. Behaviorizing portrayals of autism suggest to readers that our experiences are irrelevant and that our actions are meaningless, wrong responses to situations. This can convey to the reader that they don’t need to think about the character’s experiences, and don’t need to use their empathy to understand the link between the situation and our actions.

When people think our behaviors are meaningless, they may attempt to remove them, or to ignore or deny the impact of situations on our experiences. But the responses we make to our environments are often coping skills. For example, stimming or not making eye contact can help us attend to what people are saying to us. Trying to remove coping skills without recognizing and responding to their purpose is harmful. Removing behaviors that we enjoy, when they are not hurting anyone else, is harmful.

The best portrayals of autistic characters that I’ve read show their experiences. They show the situation we are actually experiencing, not the one a non-autistic character or the (assumed) non-autistic reader would experience. This is a humanizing portrayal of autism: It recognizes that we have internal experiences and motivations and responses. A humanizing portrayal of autism can require thinking (sometimes pretty hard) about what experiences are like for autistic characters, so that you can show those experiences as the links between our situations and our responses. It’s also good practice in general to know what your characters’ motivations are and why they do what they do.

Note that some portrayals are intermediate between behaviorizing and humanizing, or shift back and forth throughout a book.

Some concrete examples

Here are some examples of the kind of thing I’m talking about:

- Behaviorizing portrayal: Brianna would scream whenever she had a wrinkle in her sock.

(Non-autistic kids typically do not do this, so the unusualness is located in the action of screaming. Because Brianna’s experience is left out, the only thing the reader sees is “mildly uncomfortable situation” and “completely disproportionate behavior”.)

- Partially behaviorizing portrayal (some experience is mentioned, but behavior is still portrayed as unusual): Brianna was especially sensitive to how her clothing felt, so she would scream whenever she had a wrinkle in her sock.

(Screaming in response to a wrinkle in your sock is still shown as unusual, although the role of experience is alluded to. Partially behaviorizing portrayals like this often involve describing needs as preferences or character traits that are not intense enough to make the character’s response understandable.)

- Humanizing portrayal: Wrinkles in Brianna’s socks grated on her nerves like sandpaper on raw skin. Brianna often had difficulty conveying how unpleasant this was to other people, and when it happened, it reminded her of all the times she’d tried to communicate her frustration and been ignored. The combination of pain and stress and knowing she would likely be ignored again stripped her words from her and left her with no other way to communicate but screaming.

(This compares Brianna’s experience to something that non-autistic readers can access – sandpaper on raw skin – and describes the link between experience and behavior, and the link between how we are treated and our ability to function.)

When your autistic character is the protagonist

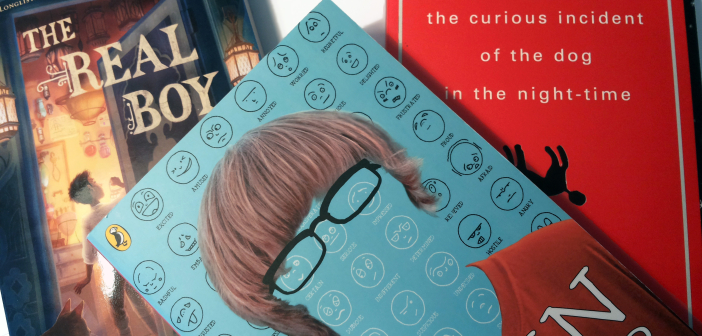

If the autistic character is the protagonist, you can directly give their internal experiences voice and depth. Anne Ursu’s The Real Boy describes social cognition difficulties in a humanizing way:

[T]heir faces all moved in different ways and their voices did all different things, their bodies were all over the place, and nothing meant anything from one person to the next. They said words they did not mean, and their conversations seemed to follow all kinds of rules – rules that no one had ever explained to Oscar. And if that weren’t enough, people talked in other ways, too, ways that had nothing to do with the things coming out of their mouths.

This is an experience in which it is entirely reasonable to have difficulty making socially expected responses to other people, which Oscar does on a number of occasions.

Here are two partially behaviorizing portrayals (note that both these books have some humanizing portrayals, as well):

From Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time:

And Mother put her arms around me and said, ‘Christopher, Christopher, Christopher.’ And I pushed her away because she was grabbing me and I didn’t like it, and I pushed really hard and I fell over.

From Ashley Edward Miller and Zack Stentz’s Colin Fischer:

Colin didn’t like to be touched by anyone, even his parents, although he was tolerant if given proper notice. On some level, he understood their need for contact. He had read about it in a book.

Neither of these portrayals references the sensory or emotional aspects of why someone would actively reject being touched. The autistic people I know who are averse to touch tend to describe it as actively painful, not just a dislike. Touch can be painful, overwhelming, intrusive, and when the autistic person has indicated they do not want it, a violation of consent. It is not uncommon for it to occur frequently despite the person’s expressed wishes, and repeated violations of consent can cause a great deal of distress.

When your autistic character is not the protagonist

What if the autistic character is not the protagonist? You can still show their inner experiences, the same way you would with other non-protagonist characters: By having other characters interpret their behavior, or by describing their situation.

Here’s one of multiple humanizing examples from Gennifer Choldenko’s Al Capone Does My Shirts, a story about a non-autistic protagonist, Moose, with an autistic sister, Natalie. Their mother has put Natalie through multiple abusive and quack therapies to try to “fix” her. They are on their way to taking Natalie to a boarding school that Moose knows she doesn’t want to attend, when the mother sees a non-autistic toddler holding his mother’s hand and tears up.

When Natalie sees this, she curls up in a tight little ball on the wood slat seat and will not move. My mother pulls herself together and tries to sound cheerful again. ‘Natalie, honey, I have a little cold. That’s all, sweet pea. Now, come on, sweetheart! This is a wonderful day!’ Her voice sounds fake and Natalie knows it. She pulls her knees tighter into herself.

Moose (the narrator) is attributing internal experiences to Natalie and correctly inferring her emotional state from her reactions and what he knows about how his mother treats her. Not just that, but in this book, even the mother knows that Natalie has internal states, as evidenced by her lying to Natalie about having a cold instead of being upset.

Contrast this with a scene in Cynthia Lord’s Rules, where the main character, Catherine, describes her autistic brother David:

David’s got lots [of rules]. One is, the cellar door always has to be shut. Even if I’m only going downstairs to grab something, he’ll race over and shut the door. Once he even locked it and I got stuck down there with a bunch of spiders until Mom heard me yelling. And the worst part is, it’s not just our house. David’ll hunt through other people’s houses, too.

There’s a plausible internal-experience explanation for this that no one in the book makes: David is terrified of cellars. But it’s described as a “rule” that he attempts to implement even in situations where it’s especially inappropriate, like the house not having a cellar. Throughout the book, no one – not the sister or the mother or the father – investigates or mentions why he might be having this response.

When your autistic character’s own motivations are obscure to them

What if the autistic character doesn’t know why they’re doing what they’re doing? Non-autistic characters also sometimes don’t have insight into why they do something, and you can handle it in the same way you would handle it with non-autistic characters: Make it clear to the reader via describing their emotional reactions in combination with relevant aspects of the situation, or show them figuring it out at a later time.

Don’t overdo it

Humanizing portrayals include leaving us human. If you focus on explaining every thought and action we have, it can have the opposite effect – it can make us look like we’re bizarre alien creatures in need of explaining. This can be especially jarring if your protagonist is narrating in first person. Autistic people are usually experiencing our days, rather than dissecting our thought processes for non-autistic readers! This is the difference between “The social event was painfully loud, chaotic, and exhausting for me, so I left early; I really wish we could have social events in quieter places” and “Because autism makes me experience sounds as excessively loud and leads to difficulty discriminating relevant sounds from background noise, I have to do more auditory processing than non-autistic people, which tires me out more quickly, and so I left earlier.” (If I’m actually explaining to a non-autistic person how being autistic impacts how I process things, I might do the latter – but when I’m thinking to myself about my experience, I’m usually thinking about my experience, not about myself.)

The most effective way to do a humanizing portrayal is to show the actual situation we are experiencing. If you do that, a lot of other things fall into place for the reader, because our responses are reasonable responses to unusual experiences. You might still need some extra explanation to connect the situation to our responses, both because non-autistic readers may not always make the connection, and because it can show your autistic readers that you “get” why we’re doing something. It lets us recognize and connect with the character. But, you don’t want to overdo it.

Learning about autistic people’s internal experiences

If you are not used to thinking about autistic people’s experiences of situations, or have difficulty imagining the experiences that make “autistic behaviors” understandable responses, reading work by autistic people can be really helpful. (Likewise if you are an autistic author who is writing about characters who are different enough from you!) There are a number of online resources and some books that are good for this, including ones written by nonverbal autistic people.

A complementary approach is to start from the assumption that their behavior is reasonable. Ask yourself: If I saw a non-autistic person acting this way, what would I infer about what they’re experiencing? If they can’t look someone in the eye, maybe that person makes them anxious. If they’re engaging in some behavior over and over, maybe they’re having fun. If they’re crying and screaming, they may be overwhelmed beyond their ability to cope. What is their internal experience like in those situations? What sensory impressions and what emotional experiences are they having?

A final note

Whether your non-autistic characters are behaviorizing or humanizing toward your autistic character(s) makes a big difference. Please consider portraying at least some of them as humanizing autistic people, and responding to your autistic characters accordingly, especially when the situation calls for sympathy! It sends a message to your readers (including your autistic readers) about how autistic people should be treated – as real people with inner experiences who do things for reasons.

The author would like to thank Michael Cohn for coming up with the behaviorizing vs humanizing terminology.

23 Comments

I really like your argument that autistic people — like all people — mostly behave in ways that make sense to themselves. Because there are so many alienating portrayals, and because autistic people are so often excluded from conversations about autism, it’s easy for me to see how even a sympathetic author could get the idea that autism is largely about strange, uncontrollable behaviors (and this would be reinforced by doing background research from seemingly credible sources). I hope that authors new to autism, and ones who have written behaviorizing portrayals in the past, are excited by the idea of exploring a new area of human experience!

I can’t help but cringe when I come across a ‘stereotypically autistic’ character in books/TV shows/etc – of the Sheldon Cooper kind. It makes us look uncaring and portrays us as having little emotions. Like robots. It’s a flaw to writers who are unaccustomed to Autism.

Rather than the fact that we have important experiences and emotions just like everyone else.

I actually love Sheldon Cooper. Having Asperger’s Syndrome I see him as being an extreme version of myself. The great thing about Sheldon is that it is never actually said that he’s autistic. It is up to the viewers interpretation.

Pingback: Resources on “Writing the Other” | Kink Praxis

This is excellent. You really go into detail and clearly explain your reasoning. I have a friend who is writing an autistic character; I’ll pass it on to her. Honestly, I think this should be required reading for anyone who wants to write an autistic character.

Pingback: Autism News, 2015/05/11 | Ada Hoffmann

“Behaviorizing” versus “humanizing” is such a great way to describe this. People don’t seem to notice that they’re opposites, but they are.

Pingback: Autistic Representation and Real-Life Consequences: An In-Depth Look

Pingback: How to Write a Disabled Character | My Blog

This was very helpful. When I first began my current writing project with an autistic main character, I thought it would be so simple, writing about someone like me, what could be easier? Well turns out the toughest thing is to stand outside of myself and really figure out what I’m all about, what makes me different, what do I need to explain and how? I was running the risk of writing a clinical pamphlet about autism rather than writing about a character with any reality or depth to him.

Thank you so much for this. I am currently writing a piece in which one of my supporting characters is autistic and I was having a hard time portraying them without it feeling forced or fake. Plus, I didn’t want to make assumptions about something I’ve never experienced. Although I don’t have autism myself, I have struggled with severe OCD for most of my life, so it’s nice to see someone showing the often overlooked reasons for the way those with mental disorders behave.

I am glad you wrote this. I read a novel about a girl on the autism spectrum, and I wanted to cringe… I did cringe. The character wasn’t humanized and depicted (at least in my opinion and my partners) as inappropriate, a burden, etc. Very well written article. Thank you!

Samantha Craft of Everyday Aspergers

Pingback: Netflix, ABC Portrayals Of Autism Still Fall Short, Critics Say - Dekalb Chronicle

Pingback: New TV Series From Netflix And ABC Feature Main Characters With Autism : Health News : NPR | My Hana

It sounds good, but I just have trouble with writing dialogue for a character with autism. Any advice?

This blog was written in 2015, and it takes me until 2018 to find it. Same question, same wording choice, a late-as-hell Google.

This makes it so much easier with the examples! Thank you!

hello! I’ve been developing a character and I’ve started to notice that she portrayed a lot of autistic traits without me meaning to, so I’ve been trying to find some good resources to see if it would be bad for me to write her as someone w/ autism in mind.

I don’t have autism myself and I was extremely hesitant to officially have her as autistic because I was afraid that she would end up as another stereotype, (since she can be very easy to write as a cringy stereotype).

This helps me a lot though, and I’ll still be doing more research on this topic but this is one of the most helpful resources! Thank you!

Hi Lacie,

I found myself in exactly the same position. As my protagonist developed it became clear to me that she was on the autistic spectrum. I have stuck with this but as you say, it has been challenging. This article is a great help. I would welcome an exchange with you as fellow writers.

I know that this article is old, but I just wanted to say that it was super helpful! I’m writing an autistic young adult character, and this really gave me good insight on how to portray them well. Thank you!

i have a question. do you have any tips on writing an autistic character in a graphic novel whose focus is not on autism but the main character happens to be autistic?

This is such a helpful article! The protagonist of my novel is autistic. He’s heavily based on my best friend, who is also autistic, but even though my best friend has done his best to try and explain his experiences to me there were still some things I didn’t know how to portray. This certainly helped clear up things. Thank you so much!

Pingback: Blossoming – Autism: Explorations

Thank you for this! I’m thinking of making an autistc oc and this has helped me realize that the “quirks” autistic people have have reasonable explanations. They have different inner sensory experiences, therefore act in a way thats soothing for them, but social pressure and past criticism and negative experiences might affect how they react to their inner experiences. That is so useful for a non-autistic person like me. Amazing article!