A Semi-Constant Waiting Game

Today we get most forms of entertainment at the push of a button, so we tend to hate having to wait. The situation is even worse if you can’t read print—resulting in an endless waiting game for blind readers.

Today we get most forms of entertainment at the push of a button, so we tend to hate having to wait. The situation is even worse if you can’t read print—resulting in an endless waiting game for blind readers.

Science fiction and fantasy tell us that anything can happen, and yet disabled people are often told that their narratives don’t fit into the genres.

What about readers like me, who never see their own illnesses depicted? To see story after story where depression draws a straight line to suicide is, for better or for worse, expressing that depression only functions in one way.

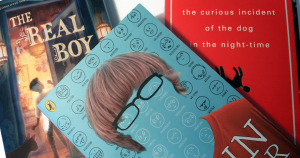

Autistic people learn, change, and cope like anyone else. However, when a character is autistic, many authors appear to see only one route for character growth: effectively making the character less autistic.

My name is Philip and I write to communicate. Authors who write about us should first learn from us; in their stories, they should present us as whole characters with interests and personalities.

An exceptionalist narrative might, at first glance, seem like a positive or even empowering one. But, as it always goes when it comes to depictions of disability, the situation is much more complicated than that-

The “autism voice”—characterized by narrative devices and a detached character voice—tends to portray autistic characters as unworldly, hyper-rational blank slates defined purely by a series of unusual behaviors.

When creators render a character into their world wearing an entire suit of autistic behaviors, reactions, and needs, dodging responsibility by denying the autism label only serves to hurt the population they’re representing.

Here is a key insight to creating realistic autistic characters: We do not do the visibly autistic things we do because of “autism,” full stop. Like non-autistic people, we are responding to our experiences of the world. Those experiences simply differ from those of non-autistic people.

Being autistic and also belonging to another minority might be one marginalization too many to sell children’s fiction informed by one’s own experience to a mainstream press, and that is a very sad thought.