I am a huge Patrick Ness fan, ever since The Knife of Never Letting Go came out in the UK and Ireland back in 2008. My co-workers and I have fought over ARCs of his subsequent books; they’ve been passed along with strict timelines involved. Every new Patrick Ness book has involved verbal caps lock.

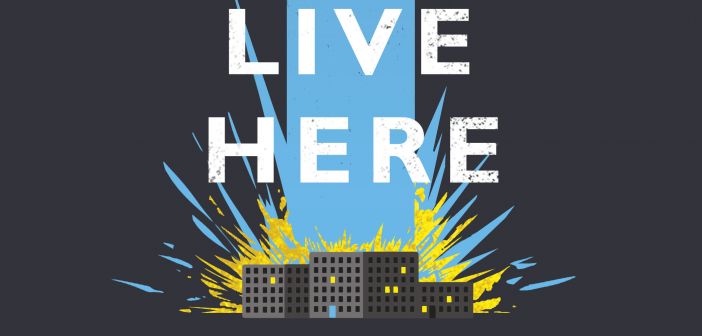

In The Rest of Us Just Live Here, Patrick Ness spoofs “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and all the Chosen One tropes. Instead of writing a novel about, well, the Chosen One, he’s written about the characters most of us would, in all likelihood, actually be: the background ones. The ones walking down the hallways; standing at lockers; hanging out after school. The ones who’d die not because of destiny, but from being at the wrong place at the wrong time. What’s not to love?

In The Rest of Us Just Live Here, Patrick Ness spoofs “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and all the Chosen One tropes. Instead of writing a novel about, well, the Chosen One, he’s written about the characters most of us would, in all likelihood, actually be: the background ones. The ones walking down the hallways; standing at lockers; hanging out after school. The ones who’d die not because of destiny, but from being at the wrong place at the wrong time. What’s not to love?

Much has been made of this book’s fantasy trope angle, even as the main characters are stressed to be absolutely, completely normal and average. They’re concerned with their troubled home lives, and grades, and how everything is going to change after graduation. But their problems are more than that: Mike, the main character, has anxiety that frequently manifests into OCD, and his sister Mel is recovering from an eating disorder. It’s implied throughout the novel that both their conditions were made substantially worse in the past due to their dysfunctional parents’ poor decisions. While Mike and Mel had recovered, Mike is starting to relapse due to the combined stress of his father’s alcoholism, his mother’s decision to return to politics, and graduation looming on the horizon.

This is one of the first times I’ve seen symptoms similar to mine—counting, rechecking, getting stuck in loops repeating something until it was “perfect”—in any book, never mind a YA one. While his symptoms are much more severe, there was a baseline that I recognised:

… and Mikey Mitchell—your humble narrator—was so tense I’d started to get trapped in compulsive loops for the first time. Counting and re-counting (and re-counting and re-counting) the contents of my sixth-grade arts cabinet. Driving our poor dog Martha crazy … by walking her over the same length of road four dozen times because I couldn’t seem to get it exactly “right,” though I could never have told you what “right” was.

Mike gets amazing support from his friends, especially his best friend Jared, who understands when to not get involved and when to step in to break a loop:

When Jared finally opens the bathroom door to see what’s going on, I’m actually crying. With fury. With embarrassment. With hate for myself and this stupid thing I can’t stop doing. I’m doing it again even now, knowing all of these things.

Jared takes one look, disappears for a sec and returns with a dry shirt, one of mine I’ve left here over the years.

The simple act of taking it from him breaks the loop.

This feeling, this self-hatred, is also familiar—like Mike I would be caught in a loop, knowing it was ridiculous, but unable to convince that tiny part of me curled tight with anxiety that I really didn’t have to do it again, again, a third time and then it would be okay. And then three times again, because then it would be done right. And then another three times, and then …

The above quote focuses on Mike’s hand washing, which is a fairly common OCD symptom that’s practically become a trope; it’s the usual one portrayed on TV and the first one many would think of if asked for a symptom. But Ness goes beyond the trope by brutally showing the consequences of constantly washing: Mike’s hands redden, and crack, and become sore as he washes them, again and again, something that’s often glossed over.

Another aspect of Mike’s anxiety is linked to how he feels his friends perceive him: deep down he feels he is the least important of them, the “damaged” friend who needs constant reassurance. He fears what will happen if he gets into a loop he can’t get out of, and they aren’t there to help him, feeding into his fear of everything changing.

One of the most interesting scenes in the book is a dialogue-only scene between Mike and his therapist, Dr. Luther. It can be an easy scene to skim, being only dialogue, but it clearly states some of the themes and problems hinted and woven throughout the novel, putting Mike in a position where he has to voice them himself. It’s also an important scene because he and his therapist decide that he should go back onto his medication. And while Mike feels that he’s failed by making this decision, Dr. Luther points out that he’s not making up his condition or how he feels, and that he’s not responsible for being this way. When Mike asks if he’ll have to be on the medication forever now, Dr. Luther replies:

“Not if you don’t want to. The decisions are entirely yours.”

“…I hate myself, Dr. Luther.”

“But not so much that you didn’t come asking for help.”

However, despite this being a respectful depiction of anxiety and OCD—at least, from my perspective—the book falls down twice on this subject near the end of the novel.

The first instance involves Jared, Mike’s best friend and the grandson of a Goddess of Cats (this provides some of the novel’s humour, in that cats literally worship Jared, from Mike’s pet cat to the local mountain lions), who levels up in healing power during the novel. But it has a catch. (Of course it has a catch). By accepting his healing power, Jared will have to leave the mortal realm and join the gods. He accepts the deal—so he can heal Mike and cure him from his anxiety and OCD. While Jared’s healing ability can be seen as the equivalent of medication, and the suggestion is given from a place of love, it jars with the previous portrayal of Mike’s slow recovery and learning to manage his anxiety.

The second instance is Mike’s response to Jared’s offer: he rejects it. (His initial reaction is that Jared could help Mel get better for good, though she also rejects it.) Not because it’s a quick fix, or because it’s not necessary—he says the medication isn’t working that well—but because if Jared healed his anxiety and OCD Mike will “[live]the rest of [his]life not knowing if [he]could have figured it out on [his]own.”

This reaction doesn’t ring true to me, especially compared to Mike returning to his therapist earlier in the novel because he needed help, and agreeing to go back on his medication. In the context of the novel, it could be seen as Mike rejecting the supernatural way out, but it can also be seen as him rejecting the outside help he’s asked for up until now, in favour of working things through on his own. Since there is still a stigma towards therapy and medication as part of treating mental health issues, and mental health is still seen as something one can combat solely through positivity, Mike’s response isn’t a full rejection of these stigmas. It’s a shame, as everything up until now was a refreshing take on anxiety in YA fiction.

These two instances unfortunately also underlie another problem in the book: the Chosen One narrative frequently jars with the more “normal” aspects of the book, such as Mike’s anxiety. In some ways, the Chosen One narrative is a good idea that doesn’t quite work with the execution. I often found myself feeling I’d prefer a more in-depth novel about Mike, Mel, Jared, and their families and friends without the supernatural elements, and that the two potentially problematic moments towards the end might not have happened if the supernatural theme hadn’t been a part of the book.

However, despite my reservations with some of the decisions Ness makes towards the end of the novel, I would still recommend The Rest of Us Just Live Here. He gets enough right in depicting Mike’s OCD and anxiety, and the fear and frustration of facing relapse, that it’s a welcome addition to YA novels involving OCD and anxiety. I also hope it will lead to more YA fantasy and SF involving contemporary issues, such as mental health, though with the speculative and contemporary threads woven together more smoothly.

4 Comments

Pingback: March in Book Bingo | A Willful Woman...

I came and read this review bc I wondering why this didn’t make the honour roll, and I guess it is because of that stuff at the end. I loved this book bc of the way it dealt both the anxiety and the needing help. Mike helping Mel is one of my favourite scenes.

The part about going on medication though was so important to me. I read it a few days after I finally decided to go on medication, after more than ten years of needing it and refusing. Reading that was so so useful in confirming that i had made the right decision. But then the ending…… ‘i won’t know if i could have beaten it without medication’ was a core reason in not wanting to go on meds in the first place. So it *did* seem to me to be a strong contrast to the rest of the book. I mean for me it served as a useful comparison to make me go ‘yup, i can see now that that idea is not helpful to me’ but it did feel at odds.

Anyway i love this book and would strongly encourage people to read it, I’m glad your review addressed the ending though <3

Pingback: The Diverse Books Reading Challenge 2017 ~ The Devil Is In The Details – Ambiguous Pieces

Pingback: The Rest of Us Just Live Here | Book Discussion Guides