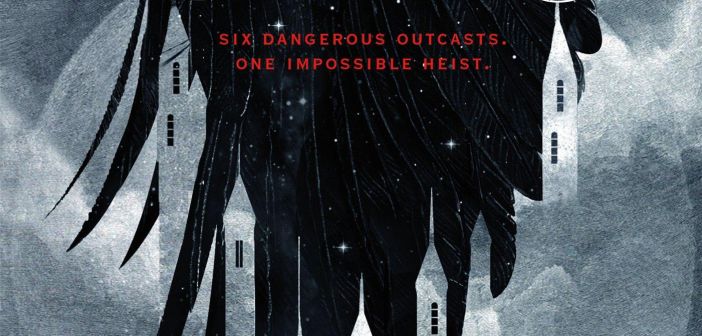

I heard dozens of good things about Leigh Bargudo’s Six of Crows before reading it, and it deserves every word. At its heart, Six of Crows is a classic heist story: a group of interesting, messed-up people facing a seemingly impossible crime—in this case, breaking a prisoner out of a high-security prison. Within this framework, Bardugo weaves together five points of view, multiple complex relationships, and an endless barrage of twists. The story is set in the same fantasy world as Bardugo’s Grisha trilogy, but it works as a standalone. After two relatively dull opening chapters that seem to mostly exist to situate readers in the world and its characters, the story is impossible to put down. It also has some of the best depictions of disability that I’ve ever read.

To my delight, Six of Crows doesn’t have only one character with only one disability. Multiple characters, both major and minor, have disabilities. Two of the five point of view characters are disabled. Kaz, the brilliant and brutal leader, has a limp, chronic pain, and trauma-related mental illness. Jesper, a loyal sharpshooter with a thirst for danger, has a gambling addiction.

To my delight, Six of Crows doesn’t have only one character with only one disability. Multiple characters, both major and minor, have disabilities. Two of the five point of view characters are disabled. Kaz, the brilliant and brutal leader, has a limp, chronic pain, and trauma-related mental illness. Jesper, a loyal sharpshooter with a thirst for danger, has a gambling addiction.

While this review will focus on Kaz’s psychological disability, I was impressed by all the representations of disability in the book. Even the ones with little page time receive respect and realism, and every disability organically feeds into the characters’ goals, backstories, and characterization. It’s common for disabilities to feel like the primary point of the character, or on the opposite end to feel tacked-on and irrelevant. The disabled characters in Six of Crows are all complex in their own rights, and it’s impossible to imagine them without their disabilities – they would be entirely different people.

For the purpose of this review, I will refer to Kaz’s symptoms as PTSD, since they roughly line up with the contemporary diagnosis of PTSD. The story itself does not use the term. As far as I could tell, the world lacks words for PTSD, as well as other neuroatypical disabilities, but the characters do indicate a general understanding that these disabilities exist – indeed, there are other mentions in the story of disabilities that have no label in the story, but that correspond with modern-day diagnoses.

Depictions of PTSD in fiction tend to manifest in very uniform ways. The boys are violent and grumpy and have panic attacks; the girls are sad and stressed and have panic attacks. Kaz, to be fair, is violent and often grumpy, but he also demonstrates PTSD traits that are often underrepresented in fictional depictions. Most notably, he experiences frequent intrusive thoughts, his mind circling back to his trauma again and again. Intrusive thoughts are one of the defining characteristics of PTSD, but I rarely see it in fiction—they just aren’t as dramatic as panic attacks. Like many traumatized people, Kaz ties tremendous emotional importance to a single mission, stemming from his trauma. While I can’t spoil the mission, it is a prime example of what I mentioned above: it seamlessly and significantly ties his trauma into his character and his motivations, without letting it define him.

The rarest PTSD symptom that Kaz displays is touch aversion. I was initially skeptical, since his touch aversion stands in the way of his romantic plotline, and there are plenty of ways for that to be problematically portrayed. However, his touch aversion makes vivid and painful sense in context, and like everything else, Bardugo treats it with the weight it deserves, rather than reducing it to a mere romantic obstacle.

Male characters with PTSD are often represented as erratic and out of control. Kaz is tightly, almost obsessively controlled, and the cases where he violently loses control feel less an issue of his PTSD and more an issue of the other stressors in his life, which struck me as both realistic and refreshing.

Since I do not walk with a limp, I cannot speak to the accuracy of Kaz’s experience, but I appreciated the differences between his relationship to his limp and his relationship to his PTSD. A single person can react very differently to different disabilities: I have some disabilities I can barely talk about, and others that don’t bother me at all. Because it is incredibly rare for a book to depict multiple disabilities, much less in the same character, these nuances rarely appear in fiction. Kaz is deeply secretive about his trauma and the related symptoms. In sharp contrast, he treats his limp with pride. This tells the audience a dozen things about the character, his injuries, and the events that caused them—and as a delightful bonus, it reminds us that disability is not a homogenous experience, even in the same character.

Disabilities are often symbolized by the tools used to help, with the most obvious example being the wheelchair as a symbol for paraplegia. Kaz has two: a cane that helps him walk, and a pair of gloves that shield him from physical contact. He recognizes that they are symbols and he uses that to his advantage. His cane “became a declaration. There was no part of him that was not broken, that had not healed wrong, and there was no part of him that was not stronger from having been broken.” While this could easily slip into romanticizing trauma and disability, it never does. Kaz is a fierce character, fiercer for what he’s suffered, and Bardugo never shies away from describing the suffering or its impacts, but she also makes it very clear that it’s a sign of strength rather than weakness.

The gloves, too, become a sign of strength, but his relationship with them is more complex, befitting his more complex relationship with his PTSD. Throughout the story, the cane is described as a source of comfort and relief. He simultaneously wields it as a weapon and treats it as a safety blanket. The gloves are part of the mythology Kaz builds around himself: he is referred to as Dirtyhands, and he actively encourages rumors about why he keeps his hands covered. Rather than proudly displaying a sign of a known injury, he allows people to guess, and though he eagerly cultivates a fierce reputation, he also shows signs of fear and even distaste. I thought this was a brilliant way to utilize naturally occurring symbols to illuminate both Kaz’s character and his relationships with his disabilities, and I am endlessly impressed by Bardugo’s gift for nuance.

In addition to strong representation of disability, the story also has prominent queer characters and ethnic minorities. Whether intentionally or not, Bardugo seems to employ a two out of six method: of the six primary characters, two are nonwhite, two are female, two are queer, etc. There’s plenty of intersectionality and plenty to praise. As an Indian girl, I was particularly impressed by Inej, a girl whose background seems to be an analogue of Indian / Romani culture.

My feelings were more mixed with Jesper, whose lineage is mixed between the Wandering Isles (the Ireland analogue) and Novyi Zem (the New World analogue). The ethnic analogues in the story tend to be fairly straightforward among major umbrella groups—e.g., there are clear parallels to European, East Asian, and South Asian ethnic groups. Jesper is described as “dark brown,” in contrast to Inej, who is described as “bronze.” This made me assume, perhaps falsely, that the character was meant to be black. Every fancast I have seen of him, including those reblogged by Leigh Bardugo, is black. Of course, both fancasts and my own mental image are just the imaginations of readers and not necessarily an indication of authorial intent, but both the in-book descriptions and the external interpretations leave me with the uncomfortable impression that this world’s equivalent of the Americas lacks an ethnic group that responds to the actual native people of the Americas.

It also mildly bothered me that the queer characters and queer romance in the novel gets much less attention than characters in the male/female romances, but there ends up being a good reason for that, and my fingers are crossed for the next book.

Overall, Six of Crows is both a fantastic reading experience and a fantastic depiction of PTSD and other disabilities. Since reading it, I have gone around telling friends, families, and random strangers, “READ IT READ IT READ IT NOW NOW NOW,” and I say the same to anyone reading this review.

5 Comments

I just feel I have to say THANK YOU. I only just discovered your blog and this is by far one of the most intelligent and interesting things I have ever found on the internet. I love how you’re addressing the importance of aspects in books so often brushed aside under the phrase ‘it’s just fiction’ – I’m so glad to see someone picking these things apart! What an awesome way to look at books. This is a fantastic review!

I have to put in: omg you must read the next book! All the queer romance!!!!

Pingback: The Diverse Books Reading Challenge 2017 ~ The Devil Is In The Details – Ambiguous Pieces

Pingback: Review Round Up – Six of Crows | Russell Memorial Library

Pingback: Six of Crows - Social Justice Books