Who Gets to Stay Autistic?

The world does its best to remove our autism from the mainstream narrative of life, hiding either it or us whenever possible. In the world of fiction, we often see these same attempts.

The world does its best to remove our autism from the mainstream narrative of life, hiding either it or us whenever possible. In the world of fiction, we often see these same attempts.

I’ve talked a lot about the ways my disability has affected my body image, my sexuality, my confidence, and my social interactions, and all of those things are important to consider when writing a disabled character. Today, however, I want to focus on the ways my disability affects the logistics of my life.

The most common wheelchair-using character has acquired paraplegia, but why is this particular narrative so prevalent, and at the expense of all others?

Portrayals of scoliosis in fiction often lack realism. Why is there so little reflection on the factors that affect a person’s journey?

Here is a key insight to creating realistic autistic characters: We do not do the visibly autistic things we do because of “autism,” full stop. Like non-autistic people, we are responding to our experiences of the world. Those experiences simply differ from those of non-autistic people.

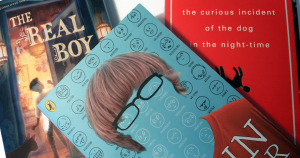

We take a moment to look back at our favorite posts and reads of the year, and to look ahead to the substantial changes 2017 will bring at Disability in Kidlit.

The two or three months I managed to get by on the reduced dose were enough to convince me: My psychiatrist is lying. I don’t need medication. I’m fine. I can beat this. Until, of course, I couldn’t.

For disabled characters, being cured is a common trope. What’s more, in most of these narratives, the characters are cured because they’re better than they were at the start of the book: kinder, gentler, braver. And finally, finally, they’re normal and whole.

A snarky New York Times column referred to CFS as “yuppie flu,” and oh, it was hilarious. Those silly rich people imagining themselves sick!

Blind characters seem to always go too far in either one direction or the other—either completely ruled by their disability, or completely unfazed. The truth is, I hate both, because neither is honest.