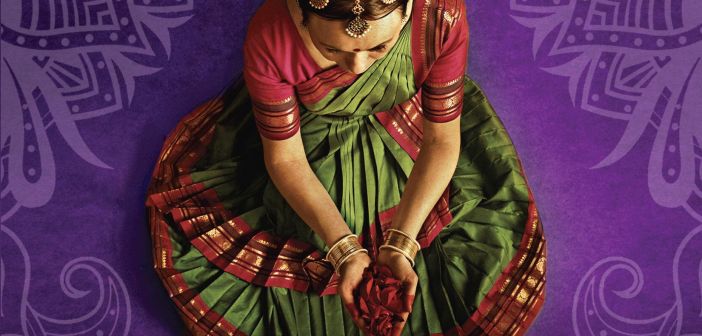

A Time to Dance is the story of Veda, a teenage dancer injured in a car accident on the way home from a dance competition. She has her right leg amputated below the knee, and is devastated when her dance teacher doesn’t want her in his class anymore.

Uday Anna puts on his most gentle tone but

some words can’t be softened.

“Veda, so many of us

blessed

with able bodies

can’t meet the demands of a professional dancer’s life.

Maybe for you

it’s time

for a new dream.”

My body hurts from my falls

But Uday Anna’s words

Hurt more. (p. 118)

When I realised this book was about a dancer who loses a leg, I was nervous. There was a part of me expecting either tragedy porn (a dancer losing a leg, gosh, isn’t amputation the worst?) or inspiration porn (she lost her leg but she’s determined to dance again! Inspiring!). However, I was pleasantly surprised. Veda isn’t a two-dimensional disabled vehicle for the able-bodied reader’s gaze. Yes, amputation takes a toll and Venkatraman explores that, but she goes beyond that too. Veda is a fully formed, likeable, realistically flawed teenager, building and navigating complex relationships with family and friends, dealing pretty well with an awful situation, and having all kinds of normal teenager-y experiences.

When I realised this book was about a dancer who loses a leg, I was nervous. There was a part of me expecting either tragedy porn (a dancer losing a leg, gosh, isn’t amputation the worst?) or inspiration porn (she lost her leg but she’s determined to dance again! Inspiring!). However, I was pleasantly surprised. Veda isn’t a two-dimensional disabled vehicle for the able-bodied reader’s gaze. Yes, amputation takes a toll and Venkatraman explores that, but she goes beyond that too. Veda is a fully formed, likeable, realistically flawed teenager, building and navigating complex relationships with family and friends, dealing pretty well with an awful situation, and having all kinds of normal teenager-y experiences.

The parts of the book that do explore losing a leg were difficult for me to read, but very realistic. This is easily the best representation of an amputee’s experience that I’ve ever come across in fiction. I was surprised to learn that the author wasn’t an amputee, because she’s written Veda’s experience so well. It’s obvious Padma Venkatraman has done extensive research, and her acknowledgements make it clear she’s worked with amputees and health professionals as beta readers. In one scene, Veda’s prosthetist, Jim, uses plaster of Paris mixed with water to make a mold of her residual limb, so he can make a clear, plastic trial limb to see how it fits. That’s pretty specific! These sorts of realistic details were present throughout.

But Venkatraman doesn’t just get the details right; she captures so much of the emotion that comes with having a limb amputated and adjusting to life afterwards. For example, Veda deals with scar pain, falls, and phantom pain:

My phantom comes alive.

Beneath my right knee,

Nails scratch at invisible skin. (p. 264)

The representation was so authentic that, at times, it actually transported me back to my own experience of amputation.

I see an ugly bulge under the sheet covering my legs.

Yank off the sheet with what’s left

of my strength.

My right leg ends

in a bandage.

Foot, ankle, and nearly half of my calf,

gone.

Chopped

right off.

“No!” The nurse pulls my sheet

back over the leftover

bit of my right leg.

But I still see the

nothingness

below my right knee. (p. 37)

This scene triggered vivid memories of waking up groggy from the anaesthetic as a nine-year-old, my hand creeping down the sheet, eventually reaching the space where there was nothing, lifting the sheet and seeing my leg amputated above the knee. It was painful to remember that, but it was worth it to really see my own experiences right there on the page. Representation matters. Good representation matters.

There were things that weren’t part of my experiences—a different country and culture; a car crash instead of cancer; a below-the-knee amputation instead of above; a click/lock leg instead of a suction leg; the spiritual awakening; a passion for dance instead of reading and writing; an interest in boys instead of boys and girls—but those differences didn’t lessen my connection to Veda in any way. What we had in common was enough for me to connect deeply with Veda as a character and invest heavily in her fate.

Like Veda, I waited impatiently for my scars to heal, visited a prosthetist and slowly learned to walk, had to have my leg adjusted to improve fit and performance, had my first experience with phantom pain, got teased by some kids, and learned to navigate relationships and the world anew as a disabled person. A Time to Dance shows the frustratingly slow pace that healing and rehabilitation can take, and the physical and emotional setbacks that can hit you along the way. It delves into things that don’t change too, like the need to use crutches every night while your leg isn’t on.

Veda gets a lot of support from her family, best friend, new love interest, and new dance teacher, which is great, but one thing I wanted more of was Veda interacting with other amputees and the disabled community. There’s one scene where she meets other patients treated by her prosthetist, Jim, but it’s the one and only time she meets them and I felt like it was a lost opportunity:

I meet a girl who says she kicks the soccer ball

better with Jim’s leg than her own.

A middle-aged woman makes me laugh

as she expounds the virtues of being one-legged:

“Cuts pedicure bills in half.”

At this party …

two-legged people are in the minority.

We amputees are the norm. (p. 181)

I wanted to jump up and down when I read that final sentence. Amputees, the norm? Amazing. It’s hard to find books with one amputee, let alone a room full of them, even though in real life people with similar disabilities often find one another and spend time together, or at least share information. Sadly, we never see or hear about these people again in A Time to Dance.

Venkatraman also includes a scene where Veda finds out about famous amputee dancers from Jim. He hangs pictures of them in his office, which really motivates Veda. “I dream of my picture hanging next to Sudha Chandran’s,” she says (p. 96). This was such an important scene to me, because it showed Veda finding amputee role models, and being inspired by their example to achieve her own goals and even imagine her own future as a famous dancer. Disabled young person being inspired, guided, or informed by disabled role models and mentors? I am here for this.

One thing I’m not here for is use of the term “differently abled” in the book and acknowledgements, especially as Veda makes a point of describing it as a “kinder word” than disabled. It’s important for authors and publishers to realise that the disabled community largely use and identify with the term “disabled” and don’t see it as a negative term, though there are some individuals within the community who will feel differently. The term “differently abled” feels euphemistic and has gained little currency since it was suggested in the eighties as an alternative to “disabled.” For more information on disability terminology, please read the excellent article recently published on this site. When Veda said, “when he says I’m ‘differently abled,’ … not disabled, … he makes me feel a little less ugly” (p. 56) I felt a twinge of irritation. The author didn’t just use the term “differently abled,” she linked the term “disabled” to ugliness. I was also unimpressed by Jim’s words to Veda:

“A below-knee amputee

with faith in herself

is two-legged, not one-legged,

as far as I’m concerned.” (p. 142)

Jim’s character is great—he’s a supportive, enthusiastic prosthetist who really listens to his patient and works hard to make her an individualised leg—but it’s a shame to have him say something that equates faith in oneself with being non-disabled.

Don’t let these concerns dissuade you from reading A Time to Dance. It’s a wonderful book and I highly recommend it, especially to other amputees. By the end of A Time to Dance, Veda is approaching something close to disability pride. She finally feels comfortable enough to wear clothing that shows off her leg, and she even takes her leg off to show her students in a dance class she takes over from her love interest in the story, Govinda:

Sitting in a chair with my students crowding around me,

I take my leg off.

Let them touch it.

As I tell them about my accident

Even Uma inches forward.

“My old teacher didn’t think I could dance again.

But dance isn’t about who you are on the outside.

It’s about how you feel inside.” (p. 291)

I like that by the end of the story, Veda is saying something I’ve often said, something people don’t always understand; she wouldn’t change what happened to her, because it has helped shape who she is.

It might sound crazy,

But I’m not upset about the accident anymore.

The accident made me a different kind of dancer. (p. 290)

While I do still feel upset about losing my leg, and while being an amputee isn’t easy and can in fact be very painful and difficult, it’s part of my identity and my story.

5 Comments

Pingback: Diversity Spotlight Thursday (#3) – Chapter Adventures

Pingback: Review for A Time to Dance by Padma Venkatraman – READING (AS)(I)AN (AM)ERICA

Pingback: The Diverse Books Reading Challenge 2017 ~ The Devil Is In The Details – Ambiguous Pieces

Pingback: Review: A Time to Dance – Colorful Book Reviews

Pingback: A Time to Dance - Social Justice Books