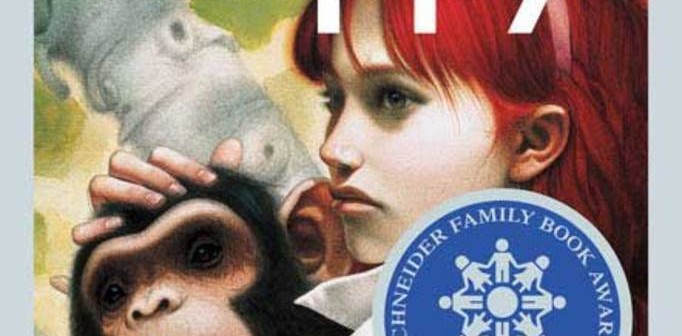

First, here is the short version of my review for Hurt Go Happy by Ginny Rorby: Yes, you want to read this book, it’s awesome. It is one of the more authentic reflections I have seen of what it can be like to grow up deaf. I found it easy to be sucked into Joey’s character and her painful yearning to have access to sign language—and, through sign language, to meaningful communication and relationships as a deaf girl growing up into a young woman.

Now, the longer version of my review:

Our protagonist, thirteen-year-old Joey, first became deaf at age six. She is being raised by a mother who will not allow her to sign and a stepfather who cares for Joey but is impossible to lipread due to his bushy facial hair. Joey’s world starts to change when she encounters a signing chimpanzee, Sukari, and Sukari’s caretaker, an older man who grew up with signing Deaf parents.

Our protagonist, thirteen-year-old Joey, first became deaf at age six. She is being raised by a mother who will not allow her to sign and a stepfather who cares for Joey but is impossible to lipread due to his bushy facial hair. Joey’s world starts to change when she encounters a signing chimpanzee, Sukari, and Sukari’s caretaker, an older man who grew up with signing Deaf parents.

Is there some inaccurate deaf-related information in this book? Yes, a bit—for example, no, hearing loss is not really measured in percentages: it is measured in decibels. With so many real-life professionals pretending otherwise for ease of explanation, though, it’s easy to understand how that one slipped through into print. And there are other minor imperfections I could point to, but any of the issues I could raise are generally trivial and easily forgivable compared to the more significant strengths of Hurt Go Happy. An exception for readers to be aware of is one use of the “r” word about four-fifths into the book.

One of the greatest strengths of this book is that it evokes so well the pain and isolation that many deaf people feel when we are surrounded by people we can barely understand. It is easy to understand exactly why Joey, the main character, risks her mother’s anger in trying to learn sign language.

I’ll be honest: there have been times when I am tired of the trope of deaf children characters desperately trying to learn sign or convince their parents to learn. It’s been done a lot, and sometimes it feels like it’s the only story that we’re allowed to have in fiction. But it’s done so often because, sadly, it is overwhelmingly common in real life as well. We still need more stories like this one to be told.

I especially like that, although Rorby does give Joey’s story a happy ending, it is not the usual trope in which parents become unrealistically fluent in sign. Joey’s mother never learns to sign at all, but does accept that Joey needs to sign with others. Her stepfather never becomes fluent either, but slowly learns enough clumsy signs that he and Joey are finally able to establish consistent communication.

The fact that this story is a trope does not mean that people should stop telling it. People do need to continue telling this story—they just need to also tell many other stories. We need stories where the hearing parents already sign at the start of the story, because some do (like mine). We need stories where the parents don’t sign but still communicate well with their deaf child and allow them to sign with others, because that does happen. We need stories in which parents never learn to sign and never establish a strong relationship with their deaf child because of it. And we need stories in which the parents’ lack of signing skills aren’t the main focus of the story—because deaf children with non-signing parents do have other things happening in their lives.

Another great strength in Ginny Rorby’s work is that, unlike most other authors trying to write deaf characters, she does not go for the easy cop-out of making her character an impossibly good lipreader. I think most authors choose to make their deaf characters champion lipreaders as a way to evade the messy but important challenge of how to show the difficulty of lipreading, and the isolation of being cut off from others, without every scene of dialogue becoming a tedious exercise in which the deaf character repeatedly says, “What? Please say that again? Please write that down?” This can become as annoying to read as it is for a deaf person to live it in real life. But if you don’t grasp how hard most deaf people have to work to understand what hearing people say and how much we still miss, then frankly, you’re not going to understand much about deaf people.

Ginny Rorby has made Joey a moderately good lipreader, but not unrealistically good. I especially love that she makes clear that lipreading ability can vary, in part, based on who you are trying to lipread. Joey can lipread some things from some people some of the time, especially for people she finds “easy” to lipread like her mother. But she also misses a lot, especially for people she finds “hard” to lipread like her stepfather. And even with people who are normally “easy” to lipread, it becomes harder to lipread when they’re angry or when they look away in the middle of talking.

All of this means that Rorby spends more time than most authors of deaf characters wrestling with the devilishly difficult task of conveying how much Joey misses in an authentic way without becoming overly tedious. There are scenes where Rorby does very well with this, and other scenes where her valiant efforts fall a little short. But I want to be clear that the imperfect examples did not impact my enjoyment of the book or the authenticity of Joey’s character. Rather, I look at them in this review because they reflect challenges common for any author striving to present a realistic picture of how challenging lipreading is for most deaf people.

One great example for other writers to consider is this one on page 98 (location 1089 in my kindle), where a classmate (seemingly) says to Joey, “I dried two_____, _____ wood bee _____, ____ deaf ______, mug my ____ ______ enough not to hear.” Here, blanks are used, as in other dialogue in the book, to show where Joey simply missed some of the words altogether. We then learn that the classmate had actually said this: “I tried to imagine what it would be like to be deaf but I couldn’t plug my ears enough not to hear. What is it like?” The phrase “tried to” does look similar to “dried two” on the lips. And “wood bee” does look similar to “would be” and so on. So this shows accurately how similar many words look on the lips, even when a deaf person catches some of it.

The many scenes of dialogue in which words are simply blanked out, or else look similar to other words on the lips, could leave readers unfamiliar with deafness wondering how Joey lipreads anything at all. Ginny Rorby gives us the answer by showing scenes in which Joey is able to guess the gist of what people are saying by extrapolating from her background knowledge or other contextual clues. She doesn’t need to lip read precisely what her mother says to realize she is asking about certain equipment Joey needs in gathering mushrooms because she has done it before and knows about the equipment. And there are scenes where Joey reads people’s body language to realize something important has been said in conversation even when she missed what it was.

But then there are other scenes in the book where the author tells us exactly what is said, and immediately tells us that Joey missed all or most of it. Perhaps this is just me, but I found these instances awkward because I was initially thinking Joey understood fine (because all the words were there) but then had to revise my interpretation when told she didn’t. Perhaps these instances could have worked if the book had been written from an “omniscient narrator” perspective. But it’s not, it is mostly written very tightly within Joey’s point of view, so usually we are clearly meant to understand—or fail to understand—only what Joey grasps and no more.

Then there is a scene in which Joey is playing with her toddler-age brother and evidently understands most of what he says. What makes the scene especially strange is that, just a few pages later, she tells her mother that she has a lot of difficulty understanding her own brother. Toddlers do tend to be much harder to lip read than adults. (They don’t fully understand or easily remember that they need to remain facing the deaf person while talking. And they often talk faster than adults and mispronounce things.) So it is realistic for Joey to have trouble understanding her brother, but odd for her to say it so soon after a scene in which she has understood him so well.

But, again, these instances were not enough to reduce my overall opinion of this book and how it portrays the experience of a young deaf adolescent girl. This is the kind of book I wish I could have had when I was younger.

1 Comment

Dear Andrea, I’m the author of Hurt Go Happy. I’m writing to thank you for this wonderful review. I mostly appreciate your honest assessment of its flaws. I’m thrilled that you found so few. I started writing this book in 1988, and knew from the onset that portraying a deaf character would be the biggest challenge. I’m not deaf, and frankly, didn’t know a deaf person. The first thing I did was enroll in sign language classes, and read everything I could find by deaf writers, hearing parents w/ deaf children, and hearing children w/ deaf parents. In the end, it took me 18 years to research and write this book. Once again, I’m grateful for the kind, generous, and honest assessment of my success. Thank you. Ginny Rorby